Here’s a fact that will make a lot of people uncomfortable: there are venomous snakes in North Texas. When we think about pest animals, we tend to picture woodland critters like skunks, opossums, mice, and rats. But it is entirely possible for a venomous snake to wander onto your property, too!

Now, before you start stocking up on supplies and barricading yourself in your home, please know that only a handful of snake species in our neck of the woods are venomous. The four “usual suspects” include…

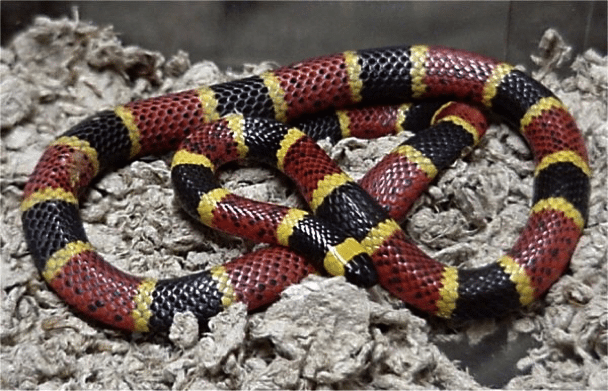

Coral Snakes

It’s hard to miss this super-colorful serpent! Coral snakes are most (in)famous for their colored bands, which appear as stripes of red, black, and yellow. Coral snakes are usually very shy and docile; it’s extremely rare for someone to receive a coral snake bite without actively handling (or provoking) the creature beforehand. However, coral snake venom is extremely potent, so only a small amount is necessary to kill a human.

While we’re on the subject of coral snakes, let’s also talk about milk snakes. Milk snakes are not venomous, but certain subspecies exhibit the same yellow, black, and red color scheme that coral snakes do. The colors are usually in a different order, though, and that’s the key to telling the two apart. Just remember these two rhymes:

- “Red and yellow, catch a fellow.” If the red stripes touch yellow stripes, the snake in question could be a venomous coral snake. Proceed with extreme caution, if at all!

- “Red and black, friend of Jack.” If the red stripes touch black stripes, the snake in question is probably a non-venomous milk snake. It’s still not a good idea to harass the snake (or interact with it at all), but you don’t need to be terrified, either.

Warning: These adages are specifically for telling the difference between coral snakes and milk snakes. They are not unbreakable laws in the animal kingdom! Not all snakes that have red markings touching yellow markings are venomous, and not all snakes that have red markings touching black markings are non-venomous!

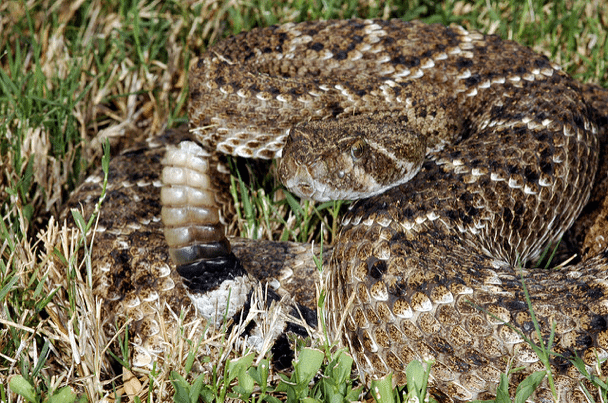

Diamondback and Timber Rattlesnakes

These snakes get their name from the distinct sound they make when agitated! The dry, eerie rattling noise that rattlesnakes produce via specialized segments in their tail is often enough to make other creatures stop in their tracks. Fortunately, this is exactly the purpose of the noise; when the snake holds up its tail and rattles, it’s trying to say, “Back off, buddy, or I’ll make you back off.” Unfortunately, a rattlesnake that’s been startled (e.g., stepped on or grabbed while it was sleeping) may strike first and “ask questions” later, and their venom is notorious for its destructive capabilities.

Rattlesnakes are usually brown or tan in color with darker markings on their backs. The scales on their tail tip have a noticeably different shape (and texture) from the scales on the rest of their bodies; those are the specialized segments we discussed in the previous paragraph. While neither kinds of rattlesnakes are common in the DFW area, they do turn up from time to time.

Cottonmouths

Also known as “water moccasins,” cottonmouths are usually (but not always) found in wet, marshy areas, including swamps, ponds, canals, and drainage ditches. They get their name from the milky-white color of the inside of their mouths. When threatened, a cottonmouth will open its mouth wide and hiss loudly, use its tail tip to shake up nearby leaves and grass (sometimes creating a rattling sound), and even coil up its body so that only its open mouth is visible. It’s certainly a dramatic display, but don’t make the mistake of assuming that they’re all bark and no bite—an agitated cottonmouth will strike and not lose any sleep over it. Interestingly enough, cottonmouths can bite while underwater. Keep that in mind the next time you go swimming!

Except for their stark-white mouths, water moccasins usually have black or dark brown bodies. They may also have visible banding, which is often easier to see on juveniles. Cottonmouths have distinctly narrow “necks” and triangular heads.

Copperheads

Copperheads have an amazing knack for blending in with their surroundings; their first instinct when they encounter a predator is to simply freeze in place and rely on natural camouflage to keep them safe. This is great for the snake but not so great for humans; a large number of cottonmouth bites occur when a person inadvertently steps/sits on the snake, picks it up, or disturbs the rock, log, or piece of trash it was hiding under! The good news is that cottonmouths don’t always inject poison when they bite, have relatively short fangs, and their venom isn’t that strong, anyway. A copperhead bite should still be considered a medical emergency, but it’s pretty rare for a person to die as a direct result of receiving one.

As their name implies, copperheads are usually coppery brown in color. Their lighter-brown bodies are decorated with darker brown markings that somewhat resemble dumbbells or (sideways) hourglasses, and like cottonmouths, they have a narrowed neck and a triangle-shaped head.

We’d be remiss to tell you about venomous snakes without also telling what you should do if you happen to be bitten by one:

- Don’t panic. Easier said than done, obviously. But panicking will raise your heart rate, which will just make the venom spread faster. The following steps should all be done quickly and with urgency, but you must try to keep a cool head!

- If possible, look at the snake before you retreat. You’ll want to put some distance between you and the snake (lest it strike again), so if it stands its ground after biting you, then move away from it yourself. But before the snake gets away from you (or you get away from the snake), try to get a good look at it. Make note of the snake’s color, its size, and where you were (e.g., in the woods, near a lake) when it bit you. Do not try to catch the snake!

- If you’re wearing rings, a watch, or any other jewelry, remove them. Snake venom usually causes swelling in the extremities, which may make removing your accessories difficult or impossible within minutes of receiving a bite wound. And if your finger/hand/wrist swells while restricted by a piece of jewelry, it could cause an entirely new (and also severe) injury.

- Do NOT attempt to tourniquet the wound, cut the wound to drain it, or suck out the poison. Despite what you may have seen on television or in movies, these are all bad ideas! Applying a tourniquet may trap the venom in one region of your body, which can lead to necrosis (and may eventually necessitate amputation of the affected area). Cutting the wound won’t really work to remove the venom, and it will just increase bleeding and your risk of infection. And sucking out the poison is not only ineffective, but it’s also pretty darn unsanitary, too.

- Get medical attention immediately. Call 911; the dispatcher will either send an ambulance to your location or tell you which nearby hospitals have anti-venom in stock. Not all hospitals have snake anti-venom available 24/7, so don’t waste time driving yourself to a hospital if you’re not positive that they can help you! Try to give the EMTs (and doctors) a description of the snake that bit you; this will help them identify the creature and treat you accordingly.

Unless you are 100% certain that the snake in question was not venomous, you should assume that it is. Venomous snake bites can be fatal, so please don’t take any chances!

It’s worth mentioning that the vast majority of snakes you’ll probably encounter in your lifetime aren’t really dangerous—if you don’t provoke them, they won’t attack you. Like nearly all wild animals, wild snakes really want nothing more than to be left alone. Still, knowledge is power, and if you can easily identify a venomous snake, you’ll be less likely to have a bad encounter with one.

The bottom line? If you see a snake while you’re going about your business, don’t bother it. And if you see a venomous snake while you’re going about your business, take your business elsewhere!